When is it an emergency?

Though my hospital is not an “emergency” hospital, we often see and treat our own emergencies. Over the years, seeing hundreds of emergencies — many after hours — I’ve learned a lot. My first observation, one which I’ve shared before, is that most “emergencies” aren’t!

Many, if not most, of the cases rushed to an after-hours emergency hospital probably could, with some professional guidance, have waited until your regular hospital opened the next morning. Many pet owners, faced with what they think is a critical problem, often panic — especially if they have no one to talk to, so they rush in to the emergency facility. Quite frankly, I don’t blame them.

[Editor’s Note: If you think your pet may be in the midst of an emergency, and you’re unable to contact a veterinarian, don’t hesitate to get to an emergency clinic. Click here for more tips on evaluating an emergency situation.]

It’s because of this that I, or one of my associates, take our own emergency calls — to be that buffer for someone to talk to.

How will they treat my dog or cat at an emergency clinic?

Though I love the fact that these facilities are available, the emergency treatment philosophy differs from that of a non-emergency clinic. More must be done in a suspected emergency situation than would need to be done at your regular veterinarian’s clinic during a non-emergency situation. Often, especially if the problem is a true emergency, the luxury of time is lost. The conservative case management approach of having a well coordinated “game plan” may no longer be appropriate.

no longer be appropriate.

In these situations, often multiple tests and procedures need to be done in a more immediate fashion to diagnose, stabilize, and treat a critically ill patient. Emergency veterinarians are most concerned with the life-threatening ramifications of the emergency and allow the non-critical problems to take a back seat. This is called “triage,” which dictates an order in which patients and problems are handled. Once the critical, potentially life threatening, conditions are dealt with, it is often prudent to wait and make sure the patient is stabilized before attention to the non-critical problems is given.

What is considered “non-critical?”

Some of the more common (non-critical) problems that are not handled with much urgency or definitive repair until a patient is completely stabilized are probably things like:

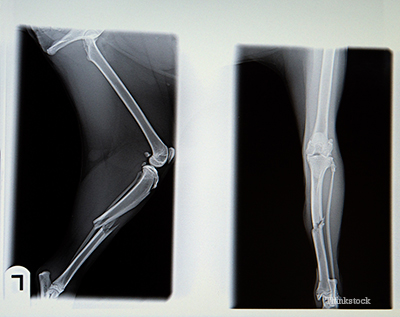

- Broken bones (most but not all)

- Skin lacerations

The truth is, broken bones are probably one of the last problems addressed by an emergency clinician because any accident or injury severe enough to break bones can also damage more critical internal organs like the heart, lungs, liver, spleen, or bladder. It’s more important to address, evaluate and treat these areas than broken bones or torn skin. I’ve seen cases where broken bones were repaired 5 to 7 days later!

Why wait to treat non-critical problems?

We recently treated a large dog that was hit by a car and had a broken front leg. On presentation, everything except the leg looked pretty good and his vitals, temperature, and attitude were great. Over the next day or so, while plans were being made with the surgeon to repair the fracture, he seemed to become a bit more sluggish and exhibited signs of abdominal tenderness that weren’t there before.

On follow up radiographs, we noted a loss of detail (the picture was more blurry than before), and an ultrasound examination revealed small amounts of fluid in his abdomen — which turned out to be urine! The impact from the car actually tore a small hole in his bladder. So clearly, the fracture took a back seat to the ruptured bladder, and we repaired the bladder first. Then, we waited a few days to make sure he was stable and that there were no more surprises. Finally, we repaired the fractured radius and ulna. Happily, he’s now doing amazingly well.

The same rules hold true for skin lacerations whether they’re from trauma or bite wounds. In these cases, it’s more important to evaluate possible internal injuries first. In cases of bites, we often don’t rush to close the wounds right away for fear that an infection will brew underneath the skin repair. Unless there’s a huge, hanging flap of tissue, we like to wait a bit and first treat the defect as an “open wound” before suturing the wound closed. Also, with bite puncture wounds, we often leave them open to drain, and let them close on their own.

I hope you never have to experience such an emergency with your pet, but if you do, I hope you now have a better understanding of how your pet’s emergency may be handled. Remember not to panic if your veterinarian doesn’t jump to fix everything right away. Trust that there is a reason for these methods.

If you have any questions or concerns, you should always visit or call your veterinarian -- they are your best resource to ensure the health and well-being of your pets.