Dr. Phil Zeltzman is a traveling, board-certified surgeon in Allentown, PA. His website is www.DrPhilZeltzman.com. He is the co-author of “Walk a Hound, Lose a Pound” (www.WalkaHound.com).

Most people have heard of hip dysplasia, which leads to hip arthritis. But elbow dyplasia?

Indeed.

Elbow dysplasia is a generic expression that mostly encompasses 3 conditions: Ununited Anconeal Process, Fragmented Coronoid Process and Osteo-Chondrosis Dissecans. But what do these fancy names mean?

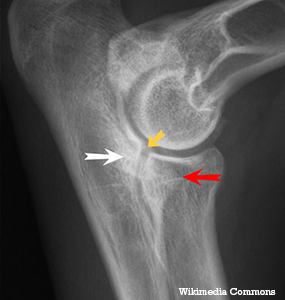

Let’s quickly review our anatomy. The elbow is a very complex joint made of 3 bones: the humerus in the arm, and the (large) radius and (small) ulna in the forearm. When these 3 bones meet to form the elbow, they should create a nice, round, smooth, happy joint, called a congruent joint.

When it is not round and smooth, the elbow is called incongruent. There will be a step between the bones. This is sometimes called elbow incongruency. In turn, it can lead to elbow arthritis and our 3 conditions termed “elbow dysplasia.” Let’s briefly go over each condition:

- Ununited Anconeal Process (UAP) is a large piece of bone that never attaches to, or detaches from, the ulna (aka “funny bone”). We end up with a typically very large piece of bone moving around in the joint.

- Fragmented Coronoid Process (FCP) is a small piece of bone that never attaches to, or detaches from, the inside of the ulna.

- Osteo-Chondrosis Dissecans (OCD) is a condition where a flap of cartilage doesn’t attach to the bone underneath. OCD is seen most frequently is the shoulder, and the outcome is typically great. It is also seen in the elbow, knee and ankle, where the outcome may not be consistently as good.

In reality, some unlucky patients can actually have two of these conditions at the same time. In each case, the loose piece of bone or cartilage acts like a pebble in your shoe: it causes pain and lameness.Itcan happen in both sides, which is why it is important to take X-rays of both legs, even though the patient is only lame on one side.

Treatment in a young patient typically entails removing the floating piece of bone or cartilage, either via arthroscopy (a tiny camera is placed in the joint) or “open” surgery (called arthrotomy, or opening of a joint). Whether one technique is better than the other remains controversial. Either way, surgery is typically successful if it is done early, i.e. before arthritis begins.

Treatment in an older patient is a little bit more difficult: there usually is quite a bit of arthritis, and whether removing the loose piece of bone will be beneficial or not is debatable. It probably depends on the surgeon, the situation and the patient.

Because this is a partially genetic disease, it is important to spay or neuter an affected dog in order to stop spreading the bad genes. This is a critical step if we collectively want to improve our dog breeds. In addition to surgery, management of arthritis is recommended for life. This includes joint supplements such as glucosamine, weight control or weight loss diets, arthritis diets, physical therapy, controlled exercise, pain medications etc.